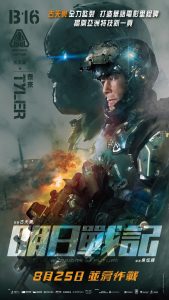

Warriors of Future: Revamping the Hollywood of the Far East

By Lok Hang Vincent Chu

Nearing the turn of the millennium, Hong Kong cinema saw an exodus of talent, one stream moving northwards to the Chinese market and another moving across the Pacific Ocean to Hollywood. It marked the end of three glorious decades when the local movie industry was known as the Hollywood of the Far East.

Despite continuous efforts to tell local stories on the silver screen, no film has come as close to putting Hong Kong back on the map as the recently released Warriors of Future. The release of this film is a milestone for Hong Kong cinema and a current event in the eyes of Hong Kong’s Cantonese-speaking moviegoers. Local media has been flooded with news regarding the film since its lead actor and executive producer, Louis Koo, promoted it at the Presentation Ceremony for the 40th Hong Kong Film Awards a month prior to the film’s local release. In an interview[1], he said:

“[The number of CGI effects in this film] exceeds any extant Asian film. I don’t want to outsource this task to overseas professionals. That’s why we have decided to hire local designers and to use local props. It’s a collaborative effort. I think this is a new page for Hong Kong cinema.”

Not only is Warriors of Future Hong Kong’s first modern sci-fi blockbuster made entirely by local talent, it is a film whose plot and special effects are on par with Hollywood blockbusters of the same calibre. This film reminds me not of a Marvel film but something out of the J.I. Joe and Pacific Rim franchises. Although it has a simple plot where a special task force is defending humanity against a formidable alien lifeform, it also develops the dynamic between the lead characters’ as well as their backstories. There were taunting comments in China saying that this film is style over substance. While I understand this reasoning, these comments are missing the point. The film does not aim to – and should not have to – tackle long-standing social issues in the way that recent instalments of the Marvel Cinematic Universe have (superficially) attempted. Instead, this film manages to tell a Hollywood-esque story without losing a vivid Hong Kong flavour. I suspect that the rift between a Hong Kong audience on the one hand, and a China audience on the other, comes down to understanding how Cantonese is used in Hong Kong. What comes off as awkward and confusing lines to China’s viewers is everyday Hong Kong-style sarcasm to us.

*Warning! The following bit contains spoilers! Proceed at your own discretion. *

More importantly, the language works marvellously with the special effects, faithfully representing Hong Kong as a place where East meets West. The film is not short of elements reminiscent of Hollywood sci-fi blockbusters. For instance, the battle suits worn by the leads resemble a mix between the suit worn by Channing Tatum in the first G.I. Joe film and Iron Man. From the sets to the CGI weaponry and enemies, every technical part screams Hollywood, but the Cantonese-plus-English lingo gives them the aforementioned Hong Kong flavour. The film does not try too hard to restrict its language to the monolingualism of most Chinese films, which is unnatural to bilingual ears. Just as English is used in every day life, so is it also used in the film. For example, the pilots speak English when communicating in military codes with the base. However, hearing Cantonese on the silver screen is not the most intriguing experience (for it is not particularly unusual). What is most exciting to a geek like myself is the cultural references to Chinese mythology and the language in the nomenclature. For instance, in the Cantonese version of the film the robots are named after two of the most ferocious mythical beasts. From the beginning, the hint has been in plain site that they are bad news. The names of the leads also reflect their personalities and functions in the film. I appreciate the naming of Carina Lau’s Tam Bing (譚冰) the most. It is a play on the term 談兵 (manoeuvre planning) from the idiom 紙上談兵 (being a behind-the-desk commander oblivious to the practical needs on the frontline). Meanwhile, 冰 means ice. This name is the most successfully literary invention in the film as it describes both the character’s action and personality. She is an ice-cold commander who is only concerned with the objective of her mission. To those who belittle this film for lacking depth, dig deeper.

This film has equally as many nods to its predecessors in Hollywood as it has subtle references to Chinese language and culture. I implore anyone reading this to grab a ticket and support this monumental film in the history of Hong Kong cinema. For without support for this first step, we won’t get to the giant leap that comes afterwards.

[1] 朱 奕錦. “明日戰記: 古天樂科幻知識堪稱顧問 特效鏡頭創亞洲科幻片之最.” 香港01, 香港01, 2 Aug. 2022, https://www.hk01.com/%E9%9B%BB%E5%BD%B1/795088/. Accessed 2 Sep. 2022.