|

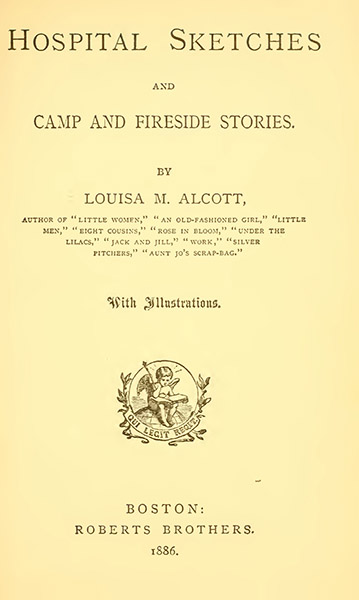

Figure 1:

Title page, Louisa M. Alcott's Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1886 first published 1863

|

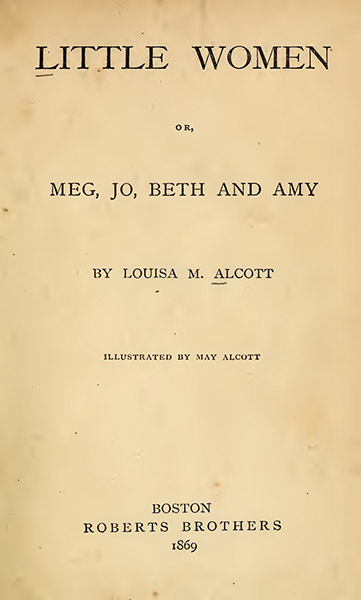

Figure 2:

Title Page of Little Women Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869

|

|

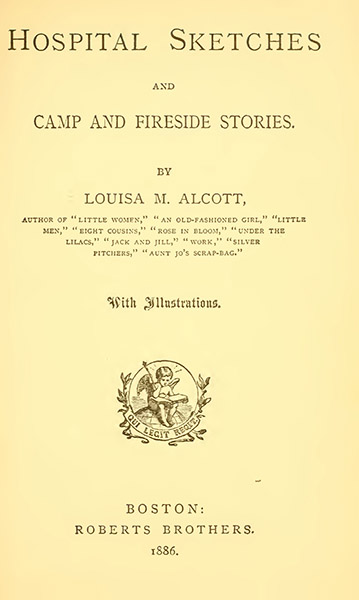

Figure 1:

Title page, Louisa M. Alcott's Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1886 first published 1863

|

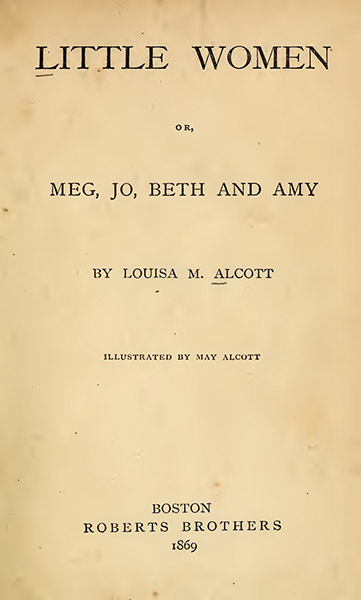

Figure 2:

Title Page of Little Women Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869

|

|

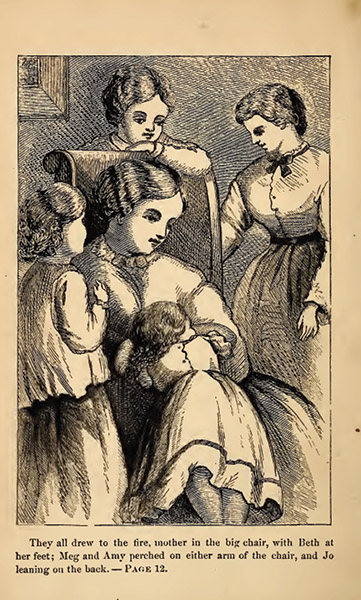

Figure 3:

Frontispiece to Little Women "They all drew to the fire, mother in the big chair, with Beth at her feet; Meg and Amy perched on either arm of the chair, and Jo leaning ont he back. -- page 12" Illustrated by May Alcott (younger sister of Louisa)

|

Little Women (1869) "You must sit still all you can, and keep your back out of sight ; the front is all right. I shall have a new ribbon for my hair, and Marmee will lend me her little pearl pin, and my new slippers are lovely, and my gloves will do, though they aren't as nice as I'd like." "Mine are spoilt with lemonade, and I can't get any new ones, so I shall have to go without," said Jo, who never troubled herself much about dress. "You must have gloves, or I won't go," cried Meg, decidedly. " Gloves are more important than anything else ; you can't dance without them, and if you don't I should be so mortified." "Then I'll stay still ; I don't care much for company dancing ; ifs no fun to go sailing round, I like to fly about and cut capers." "You can't ask mother for new ones, they are so expensive, and you are so careless. She said, when you spoilt the others, that she shouldn't get you any more this winter. Can't you fix them any way?" asked Meg, anxiously. "I can hold them crunched up in my hand, so no one will know how stained they are ; that's all I can do. No ! I’ll tell you how we can manage--each wear one good one and carry a bad one ; don't you see ? “Your hands are bigger than mine, and you will stretch my glove dreadfully," began Meg, whose gloves were a tender point with her. "Then I'll go without. I don't care what people say," cried Jo, taking up her book. "You may have it, you may ! only don't stain it, and do behave nicely ; don't put your hands behind you, or stare, or say 'Christopher Columbus' will you?" " Don't worry about me ; I'll be as prim as a dish, and not get into any scrapes, if I can help it. Now go and answer your note, and let me finish this splendid story." (1869 edition, p. 40-41) |

|

Figure 4:

"John" "John." The manliest man among my forty.-- Page 53.

Figure 5: "One hand..." "One hand stirred gruel for sick America and the other hugged baby Africa" - Page 76

|

Hospital Sketches (1886 edition) "I want something to do" (3). "Bless you, no child; it's the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in fifteen minutes." "What shall we have to do? " "Wash, dress, feed, warm and nurse them for the next three months, I dare say. Eighty beds are ready, and we were getting impatient for the men to come. Now you will begin to see hospital life in earnest, for you won't probably find time to sit down all day, and may think yourself fortunate if you get to bed by midnight. Come to me in the ball-room when you are ready; the worst cases are always carred there, and I shall need your help." (25-26) The first thing I met was a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose, and took it by storm. Cologne, with its seven and seventy evil savors, was a posybed to it ; and the worst of this affliction was, every one had assured me that it was a chronic weakness of all hospitals, and I must bear it. I did, armed with lavender water, with which I so besprinkled myself and premises, that I was soon known among my patients as "the nurse with the bottle." Having been run over by three excited surgeons, bumped against by migratory coal-lids, water-pails, and small boys, nearly scalded by an avalanche of newly-filled tea-pots, and hopelessly entangled in a knot of colored sisters coming to wash, I progressed by slow stages up stairs and down, till the main hall was reached, and I paused to take breath and a survey. There they were! "our brave boys," as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name, [end 27] with an uncomplainlng fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each like a brother. In they came, some on stretchers, some in men's arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house. All was hurry and confusion, the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and doorways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that usually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron's motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home. The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep ; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty, which was rather "a hard road to travel" just then. The house had been a hotel before hospitals were needed, and many of the doors still bore their old names ; some not so inappropriate as might be imagined, for that ward was in truth a hall-room, if gun-shot wounds could christen it. [27-28] The amputations were reserved till the morrow, and the merciful magic of ether was not thought necessary that day, so the poor souls had to bear their pains as best they might. It is all very well to talk of the patience of woman ; and far be it from me to pluck that feather from her cap, for, heaven knows, she isn't allowed to wear many; but the patient endurance of these men, under trials of the flesh, was truly wonderful Their fortitude seemed contagious, and scarcely a cry escaped them, though I often longed to groan for them, when pride kept their white lips shut, while great drops stood upon their foreheads, and the bed shook with the irrepressible tremor of their tortured bodies. One or two Irishmen anathematized the doctors with the frankness of their nation, and ordered the Virgin to stand by them, as if she had been the wedded Biddy to whom they could administer the poker, if she didn't ; but, as a general thing, the work went on in silence, broken only by some quiet request for roller, instruments, or plaster, a sigh from the patient, or a sympathizing murmur from the nurse. It was long past noon before these repairs were even partially made ; and, having got the bodies of my boys into something like order, the next task was to minister to their minds, by writing letters to the anxious souls at home; answering questions, reading papers, taking possession of money and valuables; for the eighth commandment was reduced to a very fragmentary condition, both by the blacks and whites, who ornamented our hospital with their presence. (37) A few minutes later, as I came in again, with fresh rollers, I saw John sitting erect, with no one to support him, while the surgeon dressed his back. I had never hitherto seen it done; for, having simpler wounds to attend to, and knowing the fidelity of the attendant, I had left John to him, thinking it might be more agreeable and safe ; for both strength and experience were needed in his case. I had forgotten that the strong man might long for the gentle tendance of a woman's hands, the sympathetic magnetism of a woman's presence, as well as the feebler souls about him. The Doctor's words caused me to reproach myself with neglect, not of any real duty perhaps, but of those little cares and kindnesses that solace homesick spirits, and make the heavy hours pass easier. John looked lonely and forsaken just then, as he sat with bent head, hands folded on his knee, and no outward sign of suffering, till, looking nearer, I saw great tears roll down and drop upon the floor. It was a new sight there ; for, though I had seen many suffer, some swore, some groaned, most endured silently, but none wept. Yet it did not seem weak, only very touching, and straightway my fear vanished, my heart opened wide and took him in, as, gathering the bent head in my arms, [end 51] as freely as if lie had been a little child, I said, " Let me help you bear it, John." [1886, 51-52] After that night, an hour of each evening that remained to him was devoted to his ease or pleasure. He could not talk much, for breath was precious, and he spoke in whispers ; but from occasional conversations, I gleaned scraps of private history which only added to the affection and respect I felt for him. Once he asked me (o write a letter, and as I settled pen and paper, I said, with an irrepressible glimmer of feminine curiosity, " Shall it be addressed to wife, or mother, John?" "Neither, ma'am; I've got no wife, and will write to mother myself when I get better. Did you think I was married because of this?" he asked, touching a plain ring he wore, and often turned thoughtfully on his finger when he lay alone. "Partly that, but more from a settled sort of look you have ; a look which young men seldom get until they marry." "I didn't know that ; but I'm not so very young, ma'am, thirty in May, and have been what you might call settled this ten years. Mother's a widow, I'm the oldest child she has, and it wouldn't do for me to marry until Lizzy has a home ol her own, and Jack's learned his trade ; for we're not rich, and I must be father to the children and husband to the dear old woman, if I can." “More shame for you, ma'am," responded Miss P[eriwinkle]. ; and, with the natural perversity of a Yankee, followed up the blow by kissing “the toad," with ardor. His face was providentially as clean and shiny as if his mamma had just polished it up with a corner of her apron and a drop from the tea-kettle spout, like old Aunt Chloe. This rash act, and the antislavery lecture that followed, while one hand stirred gruel for tack America, and the other hugged baby Africa, did not produce the cheering result which I fondly expected ; for my comrade henceforth regarded me as a dangerous fanatic, and my protegé nearly came to his death by insisting on swarming up stairs to my room, on all occasions, and being walked on like a little black spider. [1886, 76] |