Interview with Dr. Sinead Kwok

Photo credit: Dr. Sinead Kwok

by Jisu Bang and Tingcong Lin

Sinead Kwok is an early career researcher whose research interests lie in the philosophy of language and communication, the history of linguistics, semiology and semiotics, as well as translation. After obtaining a PhD, which explores Western translation theories from a semiological and semiotic viewpoint, she was offered a lecturing position by the School of English, HKU, and has been enjoying the work atmosphere. She is currently working on the relationship between textualization and sign theories, as well as turning her thesis into a book.

- Could you tell us about your area of research?

I study philosophy of language, generally speaking, which is not a common thing to do in the School of English. The linguistic strand at the School of English tends to be more sociolinguistically-oriented, in my understanding. In sociolinguistics, and any area of linguistics, deep-seated theories of language and communication presupposed by linguists’ practices and analyses are oftentimes overlooked. So, what I do is I revisit such theories, which are often just taken for granted in mainstream linguistics. I have always been interested in theory, ever since my undergraduate years.

My research examines and pushes one to rethink the theories of language and communication – those that have been passed down, reformed, or reinvented over the years – that have been taken for granted in academia as well as our daily lives. For instance, when we talk about language in terms of languages or speak of communication as meaning transfer, all those things already presuppose certain philosophies of language. We may not be aware of them, but everyone must have a philosophy of language when they engage in linguistic practices.

Integrationism, very simply put, is a theory of signs. Traditional linguistics has been based heavily on a rather rigid conception of signs. It tends to focus on the form and meaning of signs, and how they are conjoined structurally within the language system. Then you have fields like pragmatics, which allow for a wide range of semantic variations but do not exactly question the ‘shared forms’.

In contrast, Integrationism is a relatively new theory of signs which marks a departure by pointing out what conceptions of signs we may have had before or still uphold today and telling us how such conceptions may be inhibiting in our understanding of language and communication.

- What is your current, specific area of research/interest?

I still work on Integrationism, because it is a sign theory which can be applied to many different fields. I used to work on translation and a bit on animal communication. Now I am working on a chapter, which centres around the relationship between the concept of written signs and the concept of texts.

Linguistics tends to focus on an autonomous text and its potential meaning variations – considered independently from the artefact on which it is inscribed, and which brings it into being. An artefact can be a piece of paper, a wall, or anything on which a text can be written – it is more of a semiological surface than a physical one. We have to have an artefact to have a text because textualization is a semiological process where a textualized artefact arises in a sign-maker’s perspective. I am currently examining the role played by artefacts, or more specifically, the integration between texts and artefacts in the shaping of linguistics and other fields: The artifactual side of textual analysis has always been ignored in linguistics, because that’s how we do linguistics – by putting aside the material influence and treating words as abstract entities. My research, then, deals with this forsaken side of textualization and its implications for linguistics and its neighbouring fields.

- Why HKU? Is HKU a good place to do what you do?

I did my PhD at HKU, primarily because Dr. Adrian Pablé was here. Adrian is like my senpai in Integrationism. My very first course as an undergraduate student at HKU was taught by Adrian – a theoretical course on language and communication. It was so difficult that it gave me second thoughts about going to college! But then I pulled through in the end, and in retrospect I thought it was a very stimulating course. This is where I began to realize my interest in language and communication theories. I didn’t think about options other than HKU when applying for graduate school. I thought Adrian would be the perfect person to guide me through my project on Integrationism – and he really was. Also, because Integrationism is not something that you can find in any university, I would say that HKU is a good place to study what I do, given how it is one of the ‘strongholds’ of integrationist teachings.

- How does it feel to turn from a graduate student to a faculty member?

For me, it is a change that feels both natural and magical at the same time. For me at least, I don’t experience any dramatic change in job nature between the two stages – I am now working on similar tasks and similar research areas to my graduate studies. It’s also a magical experience to teach courses I have taken as a student. I was there (sitting in the classroom), and now I am here (teaching). Also, my experience as a student is very helpful to me when I try to understand the courses from a student’s perspective.

- What are your interests outside of academia?

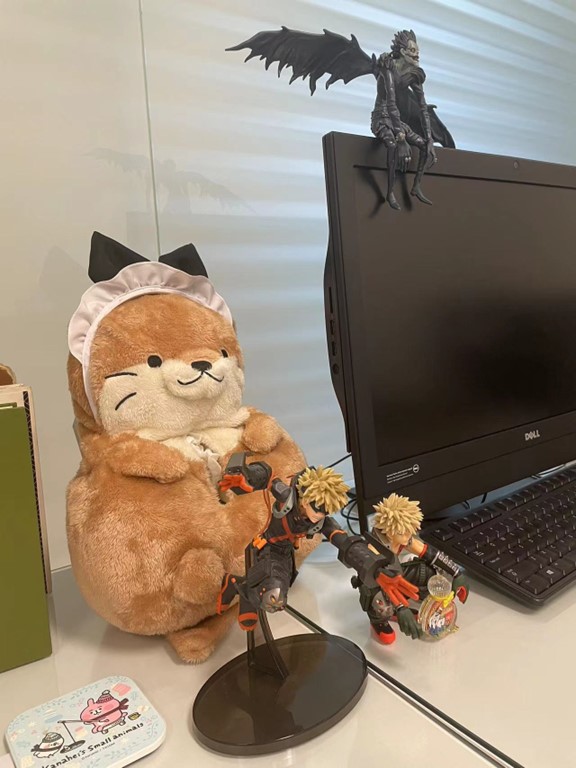

It is difficult to maintain a hobby in academia – people are busy (laughs). I am quite an “otaku” myself. I am very into Japanese cultures. I also like listening to music (especially metal) and gaming. I particularly enjoy using anime or games as examples in my classes for my demonstration of course content or for discussion.

- Do you have any advice for graduate students on career planning or study and research in general?

I feel that graduate students are often haunted by having too much freedom, which can make it difficult for them to plan their work or work as they have planned. So the key to doing postgraduate research is self-discipline, and never losing sight of what you are trying to do. As for career planning, I’d say, don’t let the degree restrict your future development. There are many possibilities, many options, and no fixed track.